Vol. 07: Field Notes from 228 Programming

Can one be passionate about the just, the ideal, the sublime, and the holy, and yet commit to no labor in its cause? I don’t think so.

This newsletter and my novel manuscript are embroiled in what feels like a zero-sum game — if I procrastinate on my manuscript, my newsletter flourishes; if I lock in and commit my precious spare minutes to the manuscript, I miss January’s edition and rush to finish February’s in its last week. But writing anything at all makes me so proud. Thank you for reading these.

We recently wrapped another intergenerational Taiwanese American Book Club series, this time focused on Kim Liao’s sublime “Where Every Ghost Has a Name: A Memoir of Taiwanese Independence.” More to come below, but I’m so happy to have found a modality that nourishes my desire for community (people to yap with and learn from) and space for slow, shy thinking. If my recent burnout has stemmed from trying to be everything to everyone, I am healing by finding my place in this big, intense work.

Here is a recording of our event, beautifully moderated by Taiwanese American longtime activists Kristie Wang and Tim Chng and writer Rebecca Liu. I hope it leaves you feeling cozy and invigorated.

It’s a silly and shameful admission, but for the past few years I’ve experienced semi-annual, prolonged and intense episodes of “Sunday scaries” — around February, when my calendar fills up with Lunar New Year and 228 commemorative programming, and around May, when I am overscheduled with Asian American Heritage Month, Taiwanese American Heritage Week, and - yikes - “UN for Taiwan” activations. This is not a complaint! I believe so deeply in what I do and am so grateful! But when the things I’m honored to do begin to feel like work I dread doing, I know I have gotten horribly lost in the sauce.

I am finding my way out, though, and back into this happy, busy place of feeling invigorated by what I do, of holding onto curiosity over routine.

What I mean is this: I have been writing, in a way, about 228 for over ten years; and “organizing” for 228 often means following an established playbook of programming. I don’t just get bored, I get lazy. I regurgitate the same talking points and metaphors; I copy and paste event logistics. I miss the point of it all.

But I was inspired by an elder book club participant (who has a memoir of his own!) who commented that though Kim’s book details a history that overlaps with his and a movement he has participated in, reading it still taught him something new and profound. This is the energy and humility I’d like to practice more: to approach commemorations as opportunities to revisit and learn something new, to become wiser each time, to find another fracture to trace, another stone to turn.

So here are my 2025 field notes from another very busy season of 228 Programming.

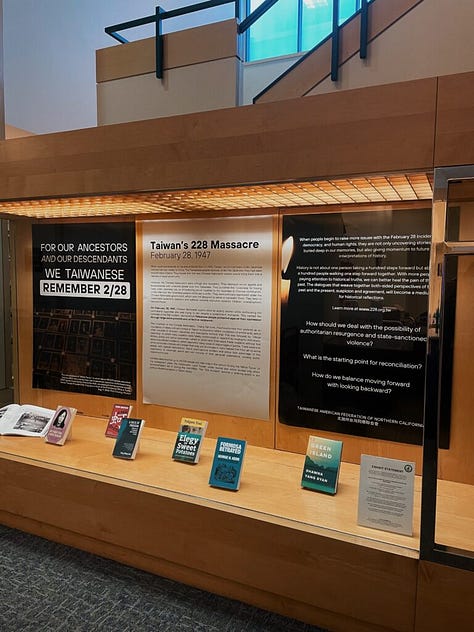

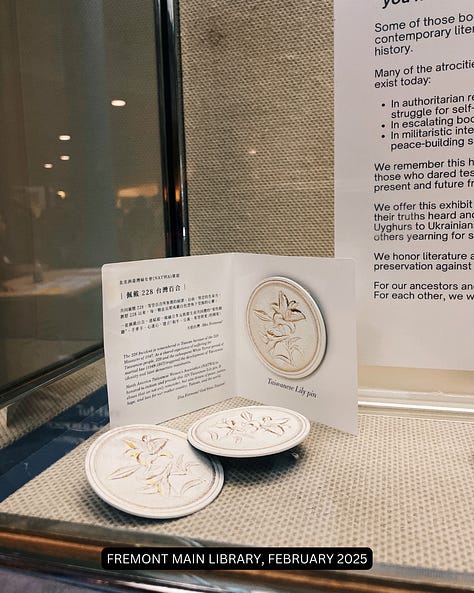

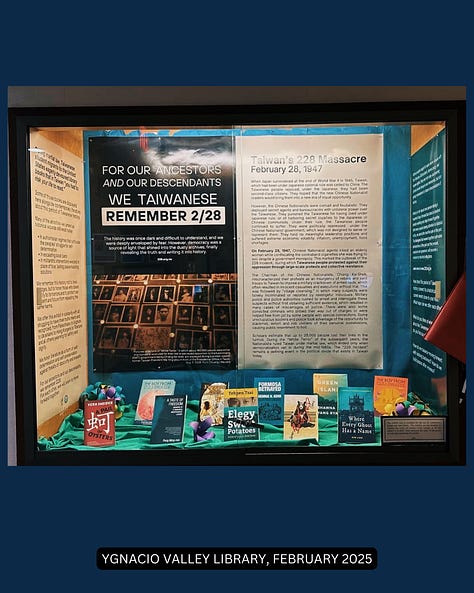

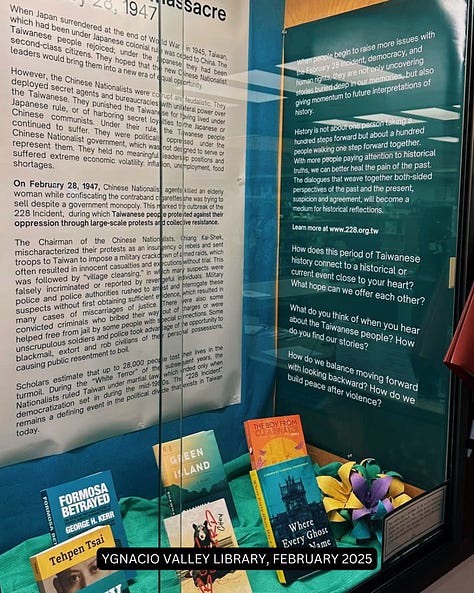

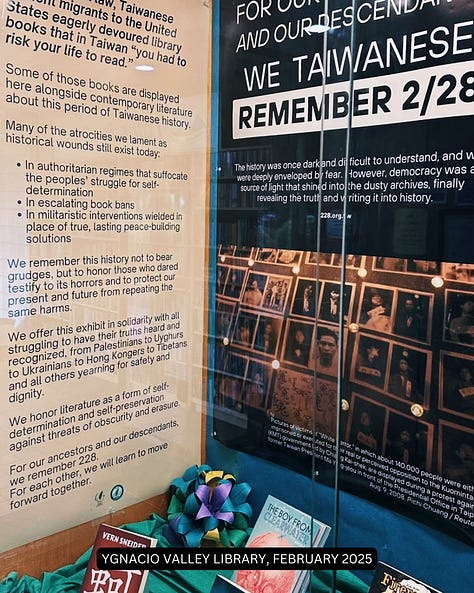

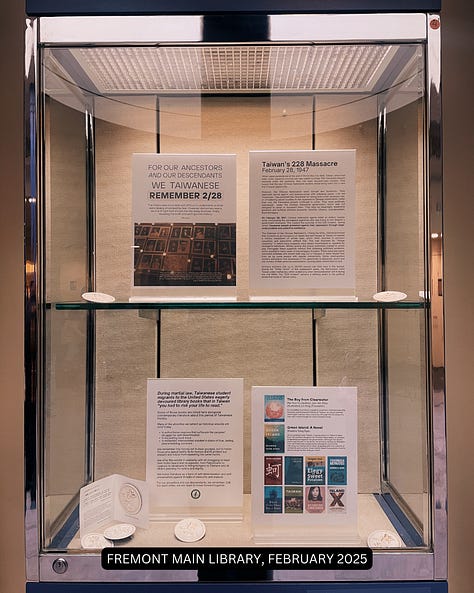

In addition to our book club series, we have two 228 Memorial Literature exhibits up for the month of February - our full display is at Ygnacio Valley Library in Walnut Creek, and a smaller version is at the Fremont Main Library lobby. I was inspired to curate this last year after our Taiwanese American book club reading of Wendy Cheng’s Island X, in which she writes about Taiwanese student migrants who came to the United States and desperately sought out library books that in Taiwan “you had to risk your life to read.” The exhibit, and its intentional placement in public libraries, honors literature as a form of self-determination and self-preservation against threats of obscurity and erasure.

I was especially pleased to present a broader collection in its second year, with additions like Kim’s “Where Every Ghost Has a Name” and the excellent English translations of “The Boy from Clearwater,” a graphic novel about a boy born during the Japanese occupation of Taiwan. (I also shyly and self-consciously added my own Book of Cord at the very last minute.)

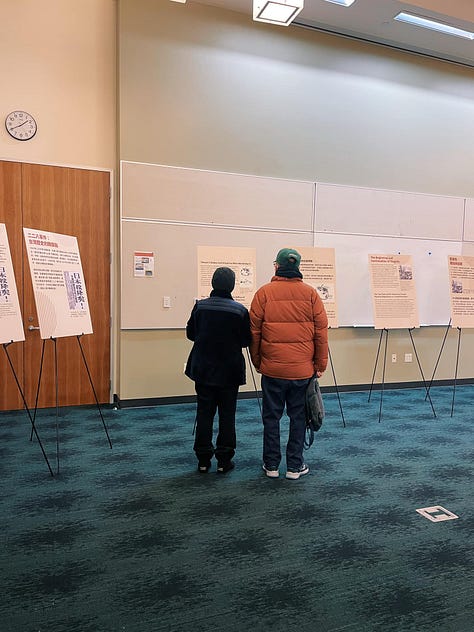

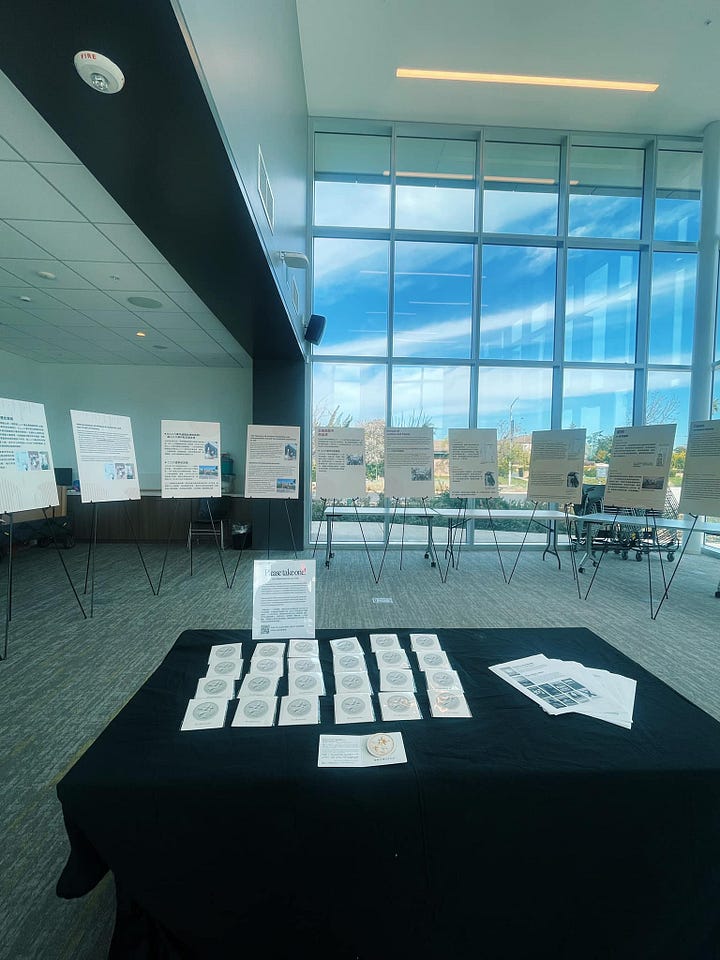

We also had several stops scheduled this year for a new bilingual educational exhibit developed by the 228 Memorial Foundation in Taiwan - at the Castro Valley Library, Newark Library, Formosan United Methodist Church in San Leandro, and two next week in Milpitas.

1947 Overture

At our Newark Library exhibit, someone wrote on our community reflection whiteboard “Listen to 1947 Overture on YouTube!” So I of course did. And I’ll link it here if you’d like to listen before you read through the rest of the newsletter.

The composition as a work and as a process is haunting, elegiac. Soon after martial law was lifted, memorial concerts for the 228 Massacre often featured Western classical music. (As it happens, one of the my earliest memories of attending a 228 memorial concert is hearing and recognizing the theme from Schindler’s List). While the music was deeply moving, this deference to Latin and German requiems also raised a critical question: did Taiwan not have its own memorial compositions?1 Such was the difficulty of building a life after totalitarianism: the older artists were still afraid, and the younger generations were left with little to learn, understand, and create upon.

But in 1993, Dr. Lin Tsung-yi commissioned Tyzen Hsiao to compose “a piece about Taiwanese history,” perhaps in tribute to his late father, Lin Mao-sheng.

Educated in Japan and then the United States, Lin Mao-sheng had returned to Taiwan, citing his “deep attachments to his homeland,” where he served as the acting dean for the College of Liberal Arts at National Taiwan University and as a committee member for the educational recruitment committee, an appointment by the Chinese Nationalist bureaucracy. His commitment to Taiwan, however, eventually undermined these prestigious posts as he criticized and offended the administration by “exposing the dark aspects of politics and society at the time.” After the 228 Incident occurred, Lin delivered a brief speech, calling for “fair and constructive” responses from the hastily formed 228 Incident Settlement Committee. A week later, armed officials arrived at his residence under the guise of an invitation from the president of National Taiwan University. He was never seen again.

A tribute written of Dr. Lin Tsung-Yi in memoriam quotes a poem that his father had written and often read to him, especially as he prepared to leave Taiwan for an education abroad. In English, the poem reads, “Where is the wonder land? It is in the deepest place of the mountain. But, we do not have to ask the fisherman how to get there. Just walk along the riverside with flowers, and you shall find it.”

As I read about both father and son, I imagine this “wonder land” as a world free from the tyranny that marked so much of their shared lives; of its near unattainability, except through great perseverance towards “the deepest place of the mountain.” I think of the instructions imbued in the last two lines — to not rely on the guidance of others, but to trust the instincts of life, beauty, integrity. I wonder if the same poem that carried Dr. Lin through his endeavors abroad was threaded in his instructions to the composer Tyzen Hsiao, who then chose to center the commission on the 228 Massacre, leading to the creation of 1947 Overture.

I played this music at our exhibit at the Formosan United Methodist Church today, and was constantly lunging for the volume controls as the music swelled from eerie calmness to powerful, shocking fanfare and timpani rolls. Be warned: this is not background music. It is epic and atmospheric, a swelling and valiant tide. At Uncle Danny’s insistence, I replayed the second section (around the 9:40 mark) again and again so he could sing along:

種一欉樹仔,在咱的土地,不是為著恨,是為著愛。

種一欉樹仔,在咱的土地,不是為著死,是為著希望。

二二八這一日,二二八這一日,你我做伙來思念失去的親人。

Plant a tree on our land,

Not for hatred, but for lovePlant a tree on our land,

Not for death, but for hope

On this day, February 28

On this day, February 28

You and I remember together the loved ones we have lost

(lyrics from poet Lee Min-yung)

I think now of the trees that poet, composer, and grieving son planted together in the wonder land, the trail of flowers they have followed, that others might still follow yet.

A Peacemaker for Taiwanese Church & Society

Ahead of the 228 Memorial Exhibit, Reverend Chou’s Taiwanese service this morning contextualized the gospel of Luke in transitional justice and reconciliation. What does it mean to love one’s enemies, to bless those who curse you, to pray for those who mistreat you within cycles of political violence? Even generations after the harm has been committed, isn’t praying for the perpetrator a betrayal of those who have suffered?

As with most things in my life, I didn’t understand some of his sermon (it is on my 2025 Bingo Card to be more diligent about my Taiwanese language fluency!) until my mom explained it to me and I filled in the rest with my own slow deep dive.

He’d shared the story of Reverend Chow Lien-hwa (周聯華), who had ministered to three generations of Chiangs - Chiang Kai-shek, Chiang Ching-kuo, Chiang Hsiao-wen (ultimately outliving them all). Here is a fascinating Taipei Times piece on the “‘palace pastor’ turned ‘society pastor,’” and though I’d like to eventually do more than cursory research (surely a pastor who preached to heads of state and “to inmates on Green Island, to the Hakka, and the aborigines”2 had a complex life and legacy! Does he by chance have a granddaughter who’d like to follow Kim Liao’s example?), this is what mattered most for today:

During and after martial law, there were many Taiwanese Christians frustrated that a dictator who exercised a regime of terrifying repression and personally signed hundreds of death sentences could claim to serve the same God as them, to abide by the same principles of mercy and goodness. From what I gather, such dissonance eventually evoked a stirring conversation in 1989 between Reverend Chow and Reverend Lu Jun-Yi (盧俊義) of the Presbyterian Church in Taiwan (PCT), who had been ministering to the very Taiwanese harmed by the Chiangs and their regime.

周牧師,您到底是講什麼道給蔣家父子兩人聽,否則他們怎會在台灣殘害這麼多人的性命?我真的很難理解。 ——盧俊義牧師

Reverend Chow, what kind of sermons did you preach to the father and son of the Chiang family? Otherwise, why would they kill so many people in Taiwan? I just cannot understand. - Reverend Lu3

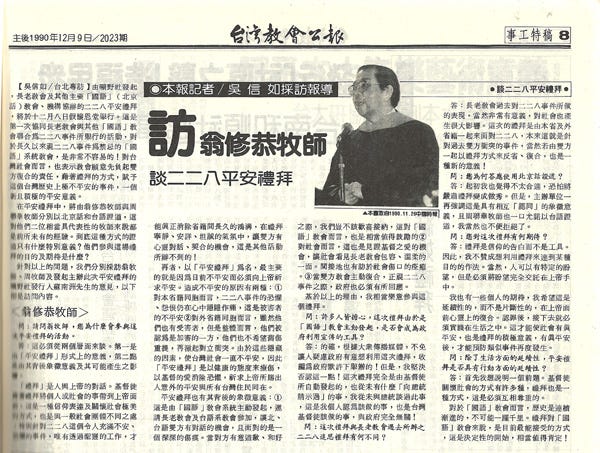

Reverend Lu had posed the question frankly, and it troubled Pastor Chow, who after a moment of deep contemplation asked what he could do. Reverend Lu suggested that before he left Taiwan, he could at least hold a service to acknowledge the victims. Reverend Chow took this to heart, and in 1990 jointly hosted a commemorative service with the PCT’s Reverend Won Hsiu-Kon, symbolizing and living out a commitment to mutual respect and peacebuilding for the people of Taiwan.

Reverend Won had been instrumental in drafting the PCT’s Human Rights Declaration (critical in Taiwan’s pursuit of national sovereignty) and counted President Lee Teng-Hui among his ministrants.

Reverend Chow delivered his sermon in Taiwanese while Reverend Won spoke in Mandarin; in doing so, “both pastors gave up their fluent mother tongues and used the unfamiliar language of their neighbors to symbolize inclusiveness and peace,” to live out the nearly impossible commandments of the gospel of Luke.4

In a later interview, Reverend Won said that "only through the work of the Holy Spirit can we truly eliminate the deep divide between ethnic groups." He hoped the service would bring lasting peace and bear witness to Christ’s love as described in Ephesians 2:14: "For he himself is our peace, who has made the two groups one and has destroyed the barrier, the dividing wall of hostility."

And in his memoir, Reverend Chow wrote that this service was the most meaningful experience of his long life. I asked my mom whether he would have dared do such a thing had Chiang Kai-shek still been alive.

“I don’t think so,” she replied.

Reading and discussing Kim Liao’s Where Every Ghost Has a Name: A Memoir of Taiwanese Independence has transformed me into a more curious and merciful student of history. Kim’s empathy for the concessions and sacrifices her “Grandpa Thomas” (🥺) made has taught me to have grace for the impossible situations people can face, the calculus only they can truly understand, their private agonies and regrets. I am sure if and when I read Reverend Chow’s writing I will find a man who tried desperately to be righteous and drew closer to Christ as he fell short again and again. I am sure none of us are brave enough to be remembered by what we’ve had to repent.

There is an affecting scene (page 275), late in Where Every Ghost Has a Name in which Kim compares her grandfather to Chiang Kai-shek as she walks through the Generalissimo’s resting place:

“I suspected that these large bronze edifices would have comforted Generalissimo Chiang about his legacy. [He and my grandfather] both had big egos. Both men probably thought they were making the world a better place and that each of them was the only man for the job he had appointed himself to: the leader of Taiwan, whatever that meant to the international community. Perhaps for all their stark differences, they had a number of common traits.”

I realized then that I relate deeply to the concurrent conceit and burden of believing I am so remarkable (the words I often evoke are “privileged, grateful, lucky”) that I cannot put down my work, I cannot falter in my pursuits, I cannot turn around.

I try not to be driven by ego, and yet I am. I try to be led by purpose, and yet so have both the cruelest and kindest people this world has known. As I scoured the internet for Reverend Chow’s memoir (which I was unable to find - please let me know if any leads!), I came across so many flattering tributes instead to his most notorious ministrant; like this one from 1971, in which Generalissimo Chiang’s spiritual reflections indicate that he had fully given himself, as instructed by his faith, to “revolutionary work… a faithful follower should be patient. Under the enemy’s heavy pressures and blows, and at a time when he is deeply anguished of spirit, he must still carry out his tasks.” His devotional is a startling contrast to another faction, the Presbyterian Church in Taiwan, whose ministry centered the history, language, and suffering of the islanders.5 (For further reading, I recommend Christine Lin’s The Presbyterian Church in Taiwan and the Advocacy of Local Autonomy, which I randomly came across during college and first learned of Thomas Liao. Full circle!)

I am Taiwanese and American. I have developed my faith in the legacy of Taiwanese theologian Reverend C.S. Song, who argued that Jesus was “for the common people” and that “our God is a political God.” His political critique led to a condemnation of the Nationalist government, and he became a theologian in exile, promoting the Taiwanese right of self determination. But I am also here, alive and lucid, in a devastating era of White Christian Nationalism.

So I am not naive enough to believe that a Christian identity is a proxy for righteousness. But I hope I am smart enough to see that only constant intellectual curiosity and humility can temper my complicity in the worst of what humans have done to each other in the name of who we love and what we worship.

I did not mean to write so extensively of my faith in these newsletters, but with every edition and every stone turned, I am gaining conviction that the story I am trying to tell is worthwhile, that though the church is not the only place where reconciliation can happen, a Taiwanese American church is one where reconciliation must happen.

In the last days of February and our commemorative programming, I’m thinking often of the kind of book I will write, the person I need to become to be capable of writing it with dignity and integrity, and what will someday be written of me, if I am so lucky.

Bonus Content:

And here is Uncle Danny in a 2018 performance of 1947 Overture in San Jose, California — if you grew up in my community or have spent time with us recently, you will recognize some folks in the choir, including FUMC’s Reverend Chou.

蕭泰然與李敏勇的悲天憫人之音—打破政治禁忌的《1947序曲》和《啊~福爾摩沙》- 顏綠芬/國立台北藝術大學音樂學系教授. 時事評析. https://www.taiwanncf.org.tw/ttforum/69/69-12.pdf

Taiwan Legendary Pastor Chou Lien-hua Dies at 96. China Christian Daily. August 8, 2016. https://chinachristiandaily.com/news/church-ministries/2016-08-09/taiwan-legendary-pastor-chou-lien-hua-dies-at-96-2069

鐵漢柔情牧師:盧俊義對周聯華的思念. 李瑞娟. Rev. Dr. Lien-hwa Chow Memorial Foundation. https://drlienhwachowfoundation.org/rev-lo/

Rev. Chow Lien-hwa, A Peace Maker For Taiwan Church And Society, Dies At 96. Taiwan Church News. August 8, 2016. https://tcnn.org.tw/en/archives/5007

Chinese Protestant Theologies of Social Ministry in Nationalist Taiwan, with Special Emphasis on the Eden Social Welfare Foundation and Liu Hsia. Maurice Alwyn Sween, III. 2006. https://ir.taitheo.org.tw/bitstream/987654321/535/1/Theologies+of+Social+Ministry+in+Taiwan.pdf

The subtitle of this edition is from a Mary Oliver poem I adore, What I have Learned So Far

“though the church is not the only place where reconciliation can happen, a Taiwanese American church is one where reconciliation must happen.”

Thank you for this moving reflection and thorough and multimodal history lesson! I had no idea that Chiang Kai-shek was a Christian and had never thought about how he might have related to his faith. Learning about Reverend Chow’s life was moving and I am also so curious how he thought about his role in Taiwan’s history. This all makes me want to learn about and reflect on the ways Buddhism has played a role in Taiwan’s democratization. Thank you for all you do in writing and organizing around 228. It is inspiring to hear how you’re approaching it with newfound curiosity.