Vol 05: Meet Lily, A (Taiwanese) American Girl

Piecing together the summer camp lore for my Taiwanese American Girl doll and her six-part historical fiction series. Just kidding... or am I?

For those familiar with both the American Girl historical canon and me, it won’t surprise you that I spend a lot of my time fever-dreaming about writing my own six-part series about an American Girl doll from the particular historical era of Taiwanese America in the late 90s/early 2000s. Of course it will follow the standard naming convention: Meet Lily, Lily Learns a Lesson, Lily’s Surprise, Happy Birthday Lily!, Lily Saves the Day, and Changes for Lily. (Obviously I wasn’t going to name her after myself, I’m definitely unhinged but even I have my limits).

However - as I’m currently backlogged with other writing projects, regrettably Lily remains a secret between you and me, and not a commercially unviable pitch to Mattel.

Still, I’m obsessed with the idea of Taiwanese American summer camps being an essential part of this American Girl doll’s lore. (It wouldn’t be unprecedented, okay? Remember Molly’s Camp Gowonagin? No? Listen to this excellent episode of Dolls of Our Lives). You’ll understand why in a bit.

My point is, historical fiction, particularly when it centered young girls (like in the American Girl and Dear America series) was profoundly influential on my literary upbringing, representing the empathic possibilities of a well-articulated collective memory. I have, in turn, relied heavily on collective memory for my writing and organizing work, trusting the narratives of Taiwanese American elder-activists to ground my identity and ideological formation.

As you know by now— this has put me in a bit of a quandary, which I attempt to publicly work through in these newsletters.

I am a slow, shy thinker and am always so excited by the imaginary conversations I host between the influences in my life - my friends, the books I’m reading, the events I attend. Lately, nearly everything has lent itself to the question of collective social memory. Stay with me! Here goes -

Collective memory refutes harmful state narratives about Taiwaneseness— this was the basis of my debut poetry collection, Book of Cord. But in the years since, I’ve come to recognize how it also fossilizes and essentializes our identities until they become spectacles disengaged from our changing surroundings.

In a recent keynote for George Washington University’s Taiwan Education & Research Program (which was very exciting for me, especially to be in conversation with such smart, wonderful people - recording below!!), I talked about the empowering possibilities of chosen ancestors and origin stories. With a constellation of collective memories, perhaps we can start to see the full, complex truth of humanity. But how often do we really see this “bigger picture”?

Through that keynote opportunity, I made a new friend who is an alumnus of Strait Talk, a non-partisan dialogue workshop that empowers young people from both sides of the Taiwan Strait to collaborate in transforming the Taiwan Strait conflict. (More on this later!) Our conversation led to an article by Strait Talk facilitator Tatsushi Arai, whose longitudinal analysis of the Strait Talk conflict resolution workshop posits the following:

Social memory stays alive when there are underlying social conditions and experiences that sustain the motivations and consciousness of individuals and groups who keep the memory alive. By implication, it also suggests that social memory becomes dormant once its underlying conditions and experiences cease to exist…

I’ve been thinking about this in the context of heritage-based summer camps, where we scratch our heads at how we are to pass on the collective memory of Taiwaneseness to a generation that would not recognize its original conditions (or even, taking a step back, should this be our task at all?). During the senior staff retreat of the Taiwanese American Foundation (TAF) summer conference a few weeks ago, I started thinking about the ways our vision parallels, and was probably informed decades ago by, Jewish American summer camps. This NPR episode by Deena Prichep, To save Jewish culture, American Jews turned to summer camp, gave some meat to my hypothesis - especially when paired with Linda Gail Arrigo’s seminal Life Patterns Among Taiwanese Americans, which posits that pro-American Taiwanese American organizations like FAPA (Formosan Association for Public Affairs) modeled themselves after the Jewish American Citizens League (the inspirational namesake of the Taiwanese American Citizens League).

So much of Prichep’s reporting echoes common narratives about TAF and similar camps (TACL-LYF, TANG):

For American Jews who are often used to being in a cultural minority, having that immersive experience can be life-changing.

"I can credit camp with my entire Jewish identity. The whole reason I stuck with Judaism was camp and the connections I made," says Frisch.

Summer camps became a way to hold onto and rebuild Jewish heritage. But in attempting to maintain Jewish traditions, these camps created a whole new form of it.

Then compare the mission and value statements of TAF, the longest-running Taiwanese American summer camp, and that of Surprise Lake Camp, one of the two oldest Jewish camps in the entire United States.

THE TAF MISSION

To foster personal growth and develop servant leaders in the Taiwanese American community for the benefit of society.

THE TAF VISION

For people of Taiwanese heritage to make a profound impact on humankind in unique and compassionate ways.

SURPRISE LAKE CAMP (Website)

We provide a high quality Jewish experience for children and young adults that is safe, fun, and promotes personal growth.

Surprise Lake Camp’s mission is to provide a high-quality camping experience primarily for Jewish children which fosters their social, moral, cultural, physical, and emotional education and development. This is achieved through wholesome recreation, Jewish ritual, environmental education, diverse program opportunities, responsible supervision, and healthful surroundings.

The history of Surprise Lake Camp, written by Jack Holman, can be read as a fascinating companion to the documentation of the Taiwanese American summer camp I grew up with, the Taiwanese American Youth Leadership camp (TAYL, now known as TACL-LYF under the aforementioned Taiwanese American Citizens League), which had originally been established by the Taiwanese Alliance for Interculture (the anchor organization of TAFNC). In TAI’s 50-year compendium, TAYL alumni Megan Chen, now in her forties, writes:

The pre-teenager in me begrudgingly consented [to attending TAYL], although secretly I was excited to meet people my age who were potentially like me. Who knew that 30 years later, I would be married to a fellow camp counselor discussing with our three kids how Taiwan is a democratic country that has a tenuous relationship with China, and poignantly so as we enter another year of Russia’s unforgettable and terrible invasion of Ukraine. The world has acknowledged the similarity between the two as examples of a larger more powerful entity wanting to exert its control over a smaller but vital and important nation. My identity as a Taiwanese American is stronger than ever and the determined spirit of my dad instilled in my youth keeps me grounded in this uncertain political climate.

In my last newsletter, I lamented that the political intention of Taiwanese American organizations has diluted over time, resulting in organizations that are socially meaningful but without the intended depth of ethnic and cultural identity formation. Which is fine if that’s what we’re all going for! But I suspect we’re still at the crossroads of figuring out, from parents and campers alike, how much of our heritage or ethnic-based communities require that we make our history — our collective social memories— alive and apparent to our diaspora? And how should we do this?

In the 80s, part of the Herzl Camp curriculum included, according to alumni Flip Frisch, “getting up in the middle of the night to reenact an escape from Nazi-controlled Germany.” I’ve heard similar anecdotes of early TAF programming abruptly shuffling campers from lectures on Taiwan’s white terror to swing choir, likely creating some dissonance, if not simply apathy. “Camps have largely abandoned those more dramatic (and potentially traumatizing) activities,” the NPR episode continues, as have most Taiwanese American summer camps. “But,”

Frisch says, “more than these very memorable recreations, she was struck by just living everyday life in a way that tied her to tradition.” I’m fascinated by how we/they achieve this, and what it means for all of us to intentionally tether to an assembled heritage.

For its part, the 2024 TAC-EC (Taiwanese American Conference - East Coast) theme centered collective memory, and vowed to “co-construct our history, reflect on how to transform our collective memory into collective action, thereby building a shared future with diverse ways of Taiwanese lives.” Notably, TAC-EC, and its youth summer conference, TANG, is the only Taiwanese American conference to truly span three generations, affording it a more robust longitudinal collective memory than many other spaces.

(There are also other points in Arai’s article about how our collective memories — “and indeed [our] realities” - shift, and how a key task of peace/conflict researchers/workers is to humanize the contexts in which disparate versions of history are expressed. More on this later, too! No time or big brain left today!!)

I also recently read Dara Horn’s “People Love Dead Jews: Reports from a Haunted Present” and found it deeply affecting. In a series of essays, Horn reflects on the mythologies of the Jewish diaspora, and how the benign ways we treat the Jewish “collective social memory” have actually presented a “profound affront to human dignity.” It is the kind of book I would want to write someday for its effectiveness to wholly earn its reader’s witness and compassion. I’m also noodling on how her work challenges me to critically separate the individual/communal desire for a safe, independent homeland from how the state of Israel violently enacts this on the diaspora’s behalf, without their explicit consent. This was a dilemma I voiced in my keynote, too — how to treat our human longings with compassion, but their contexts and consequences with critique? And for our summer conference senior staff — how to do right by (what we know of) our histories for a new generation of heirs?

The last work I’ll mention for this imaginary discourse is Minsoo Kang’s “The Melancholy of Untold History,” an exquisite work of meta-fiction in which a historian dispels a national myth and, in turn understands the power of a narrative (in other words — a collective social memory?! The gravity of myth-making?! Do you see how it all comes together?!). An excerpt I loved that I hope braids the frantic threads of this newsletter:

“The central purpose of [a unified history of the land] was to remind readers of the original unity of the people and the realm and to provide a vision for what must be recovered and repaired in order to return to a time of harmony. The accounts he collated in True Records of Past Events were ones he found most useful in putting together a coherent and continuous narrative, his' ‘unified history,’ while those in Miscellany of Past Events were ones that did not easily fit into it, because they either contradicted other pieces of evidence or were totally disconnected from them.”

Other shorter-form thoughts:

I don’t have an informed perspective on the allegations, only deep fear that in a political climate of violent xenophobia and economic anxiety, Asian Americans living in Arizona will be targeted and scapegoated as Vincent Chin was over 40 years ago.

I cling to the good news of Taiwanese moving to Arizona finding and building meaningful community with each other, as reported by the Arizona Republic last month. In particular, a struggling Chinese Baptist Church has welcomed an influx of Taiwanese families, doubling their congregation in less than two years. “The influx of Taiwanese people is likely to be felt across the Valley,” the article reports, and I am curious how this new wave of immigrant families will live out the ongoing paradox of diaspora. I wish them safety and all the comforts of community.

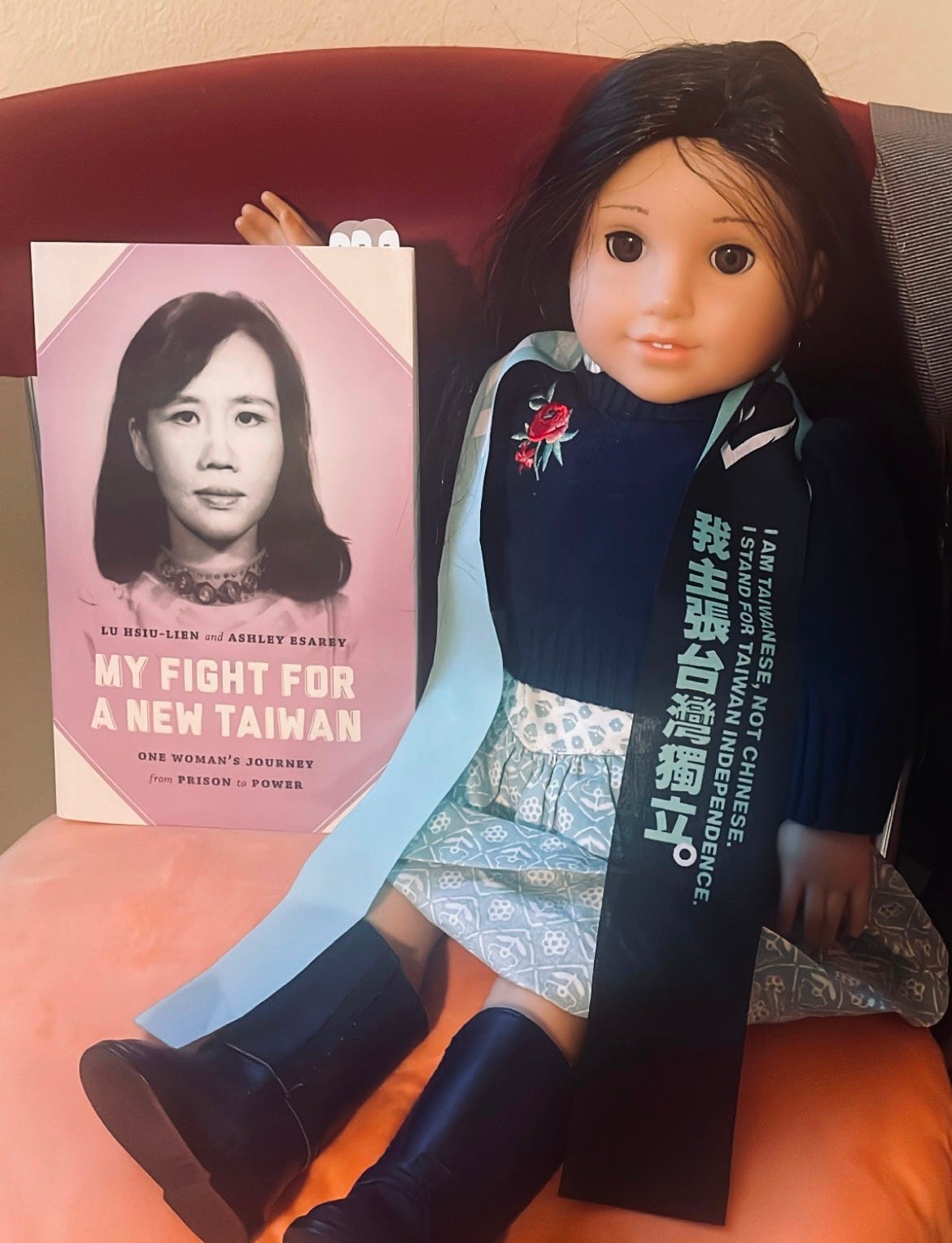

Speaking of TSMC, Taiwan’s former Vice President Annette Lu and co-founder of the North American Taiwanese Womens Association (NATWA) stopped by for a chat with her NATWA besties this week!

She’s had a slew of unpopular opinions in recent years, including her more recent criticism of Taiwan’s current Vice President Bi-khim Hsiao (then-de facto ambassador to the United States) for “abandoning” Taiwan’s crown jewel to Arizona, rather than situating her here in Silicon Valley.

This hot take was flatly rejected as a horrible take by the audience, who refreshingly treated Lu as a peer to be directly debated with (after all, many of them were her longtime friends). I also got my copy of her memoir signed! And, I don’t know, will there be a juicy plot point in my American Girl canon where Lily and her mom campaign overseas for the Chen-Lu ticket of 2000? WE SHALL SEE.

Another observation from my fieldwork in Taiwanese America: the livestreaming culture, from influencers to politicians. The DPP regularly live broadcasts political commentary in a funny-but-sad-but-cute series called #老闆叫我開直播 (Boss told me to livestream).

The DPP’s Policy Executive Director ( 政策委員會執行長) Wang Yi-Chuan 王義川 was recently in town for a keynote, which he also live-streamed, at times speaking to his online audience rather than the one in front of him. And it was kind of weird? And kind of cringe? But I get it and appreciate the commitment to accessibility? More to come as I research this. And in the interim, here’s my Taiwanese political livestream debut:

What I’m reading lately:

Taiwan Travelogue by Yang Shuang-zi, in which a fictional Japanese writer explores the colorful and complex culinary, linguistic, and political dynamics that shaped life in 1930s Taiwan.

This Strange Eventful History by Claire Messud

The First Advent in Palestine: Reversals, Resistance, and the Ongoing Complexity of Hope by Kelley Nikondeha

Related to the last and current newsletter, Birthright Journeys: Connecting Dots from the Diaspora (Andrea Lim for Dissent), linking together projects of “long-distance nationalism.” Wish I could say more but my mom/translator says these newsletters are getting too dang long.

I read this when you first posted it and I happened to come across it again. The way you think/write just makes so much sense to my brain and I love that we share so many of the same hopes for Taiwanese America! Adore the American Girl Doll as someone who also loved historical fiction centering girls as a young reader.

absolutely floored by the breadth of your work: from american girl dolls to summer camp histories to birthright reflections. so much to chew on. many blessings to your mom for doing the translation work!!!